Table of Contents

-

<

1

>

Chefs Who Contributed

to This Project -

<

2

>

Prologue:

A Journey to unravel

Tokyo’s diverse food and spirit -

<

3

>

Scene 01 - Edo : The food culture that has been

passed down from Edo to

Tokyo and its spirit -

<

4

>

Scene 02 - The Modern Era : Harmony with overseas food

culture Tokyo's unique evolution

and development -

<

5

>

Scene 03 - The Future : Sustainability and Diversity

Learning from Japan's ancient Shojin

cuisine The future of Tokyo's food

In Tokyo, you can enjoy various food cultures from all over Japan and the world, including traditional Edo-style cuisine.

In this project, we held a presentation event entitled " A Journey to unravel Tokyo’s diverse food and spirit " with the cooperation of chefs active in Tokyo in order to widely disseminate the charm of Tokyo's diverse food to travelers around the world and further attract tourists.

Foreign media participated in the event, and the chefs gave cooking demonstrations and talks on the theme of Edo, modern, and future Tokyo food, allowing them to experience the charm of Tokyo's food and share its profound charm overseas.

Concept Movie

Chefs Who Contributed

to This Project

-

Fourth-Generation Owner of Shojin Ryori Daigo

Tokyo Tourism Ambassador /

Paralympic Support Ambassador for Paris 2024Yusuke Nomura

Mr. Yusuke Nomura is the fourth-generation owner of Daigo, a long-established restaurant in Atago, Minato City, specializing in Shojin Ryori (traditional Buddhist vegetarian cuisine) served in a kaiseki-style course. He trained at a French restaurant, worked as a bartender, and holds a sommelier certification. Shojin Ryori Daigo has been featured in the Michelin Guide Tokyo for 18 consecutive years since 2007. In the 2025 edition, it was newly awarded the Michelin Green Star in recognition of its proactive efforts toward sustainable gastronomy.

-

Owner-Chef of Kishun Suzunari

Akihiko Murata

Inspired by his grandfather’s fugu restaurant in Monzen-Nakacho, Tokyo, Mr. Murata aspired to become a chef from a young age. After graduating from a commercial high school in Chiba, he trained for 13 years at the prestigious Japanese restaurant Nadaman. In 2005, he opened Kishun Suzunari.

The restaurant earned its first Michelin star in 2012 and retained it for 6 consecutive years through 2017. Known for offering authentic Japanese cuisine at reasonable prices, it enjoys broad popularity among a wide range of customers. -

Owner-Chef of Piatto Suzuki

Yahei Suzuki

Mr. Suzuki is the owner-chef of Piatto Suzuki and Trattoria Che Pacchia. He began his journey in Italian cuisine at the age of 19 under Chef Masaru Hirata. He later trained at Cucina Hirata and studied in Italy for a year from 1992, learning at a culinary school and working in restaurants across Sicily, Tuscany, Liguria, and Piedmont.

Upon returning to Japan in 1993, he became the head chef of Vino Hirata, and in 2002, he opened Piatto Suzuki.

While rooted in traditional Italian cuisine, his dishes showcase seasonal ingredients. The restaurant was awarded a Michelin star every year from 2007 to 2021. -

Owner-Chef of Kappo Funyu

Noriyuki Funyu

After graduating from culinary school, Mr. Funyu joined Nadaman Main Restaurant – Sankatei to pursue excellence in all aspects of dining, including presentation, ingredients, and service. He later worked at Japanese restaurants in Tokyo hotels and at a kappo-style restaurant in Kagurazaka. In 2011, he opened his own restaurant, Kappo Funyu.

-

Owner-Chef of AMOUR

Yusuke Goto

After graduating from the Tsuji Culinary Institute in France, Mr. Goto trained at Au Crocodile in Alsace. He later honed his skills in French cuisine at Ginza L’ecrin, returned to France at age 25, and then worked at renowned restaurants such as Quintessence and Otowa Restaurant.

At age 30, he became the head chef of Écureuil, and in 2012 was appointed executive chef of AMOUR, which opened in Nishi-Azabu. Just six months later, it earned its first Michelin star, which it held for seven consecutive years. In 2016, the restaurant relocated to Ebisu. -

Owner-Chef of Shiawase Zanmai

Kozo Nakayama

At the age of 27, Mr. Nakayama transitioned from a career as a graphic designer to becoming a chef after meeting Masahiro Kasahara, owner of Sanpi-Ryoron. As Mr. Kasahara’s first apprentice, he trained at Tori-masa and contributed to the launch of Sanpi-Ryoron in 2004.

In 2009, he opened his own restaurant, Shiawase Zanmai, in Ebisu.

The restaurant follows the Sanpi-Ryoron style, offering a single omakase course that blends seasonal vegetables and fish with creativity and finesse. His refined dishes continue to win the hearts of many diners. -

Owner-Chef of GENEI.WAGAN

Hideki Irie

Mr. Irie is the owner-chef of GENEI.WAGAN, a members-only ramen kaiseki restaurant. With a unique background as a former private detective, he entered the culinary world after being inspired by a ramen shop owner’s philosophy.

He is a dedicated researcher, having developed his own noodle-making machine and soy sauce. A frequent winner on culinary competition shows, he faced Chef Yosuke Suga on Iron Chef, and was crowned Asia Champion on Asian Ace.

At GENEI.WAGAN, he offers a different ramen experience with each visit, having created over 1,000 unique variations to date.

Prologue

A Journey to Unravel

Tokyo’s Diverse Food and Spirit

Tokyo’s cuisine is defined by one key feature: diversity.

Whether residents or visitors from across Japan and around the world, people of all races, religions, generations, and genders can enjoy a wide variety of delicious food in Tokyo.

But what makes Tokyo’s food culture so rich and varied?

Its roots lie in the Edo period. In 1603, the Tokugawa shogunate established its government in Edo (modern-day Tokyo), marking the end of a long era of civil wars. As peace returned, people began to enjoy more leisure and sought pleasure in food.

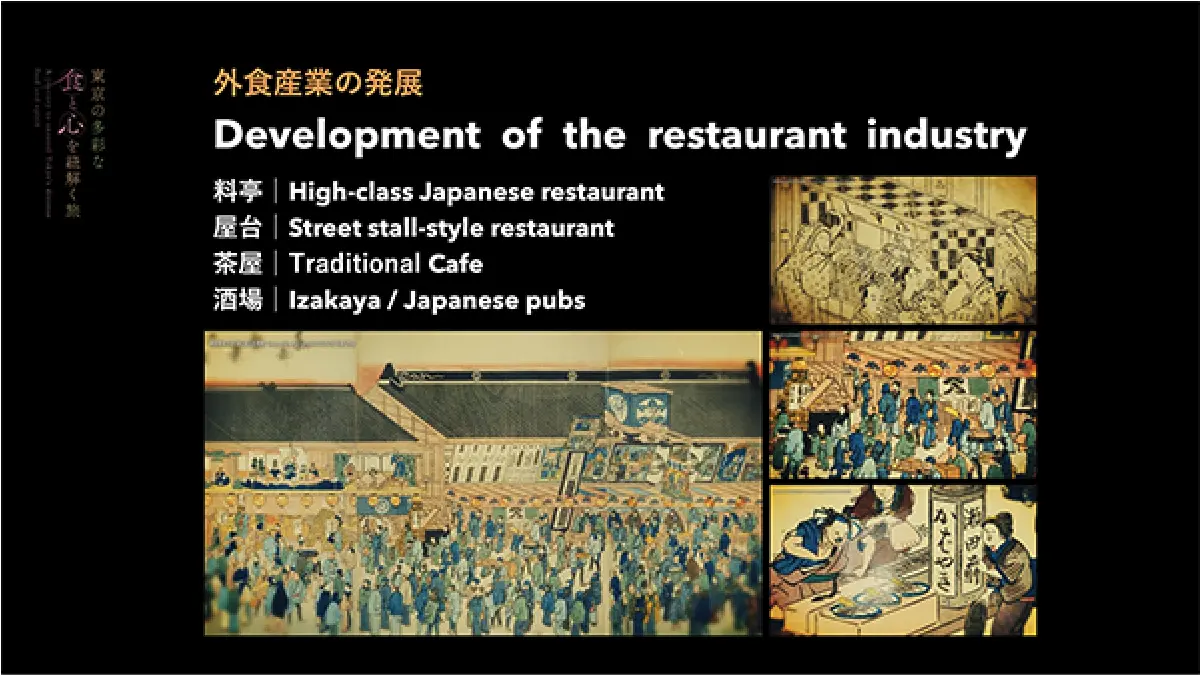

This period saw the rise of a vibrant dining-out culture in Edo, with food stalls, teahouses, and taverns thriving throughout the city.

Interestingly, while France saw the birth of modern restaurants around the time of the French Revolution in 1789—when palace chefs began opening eateries in Paris—Japan had already developed a similar culture nearly a century earlier in Edo.

Two key events in the Edo period greatly contributed to the culinary diversity seen in Tokyo today:

the construction of Edo Castle and the sankin-kotai system (alternate attendance).

The building of Edo Castle, one of the largest wooden structures of its time, brought craftsmen and workers from all over Japan to the city. Additionally, under the sankin-kotai system—where feudal lords from across Japan gathered in Edo on alternating years—these lords regularly traveled to the city, bringing with them a variety of local products and ingredients.

As a result, a wide variety of regional foods and ingredients were introduced to Edo, giving rise to its richly diverse food culture.

Taste preferences also varied by region.

In Kyoto, which is located inland, vegetable-based dishes developed using light soy sauce to highlight the colors of the vegetables. In contrast, Edo, situated near the sea, favored bold flavors using dark soy sauce to complement the richness of fresh seafood.

Water quality also played a role.

Kyoto's soft water, drawn from the mountains, is ideal for vegetable-based broths like kombu dashi. Edo’s slightly harder water, however, pairs better with animal-based broths such as katsuobushi dashi. These regional differences still influence the flavors of Kanto and Kansai cuisine today.

In the Meiji era, as Japan opened to the world, a wave of international ingredients and food cultures entered Tokyo. Meat, once forbidden during the Edo period, became part of the diet, giving rise to iconic dishes like sukiyaki, as well as the introduction of Western-style foods such as omelet rice and curry.

Tokyo’s open and evolving food culture owes much to three key values found in Buddhist teachings, known as the Three Hearts:

Daishin – A big, open heart free from fixed ideas

Kishin – A joyful and positive mindset

Roshin – A considerate heart that puts others first

These values helped Japanese people accept foreign food cultures with an open mind and adapt them into their own. Through this process of integration, Tokyo has developed a uniquely diverse food culture—one that continues to evolve and thrive today.

Scene 01 Edo

The food culture that has been passed down from

Edo to Tokyo and its spirit

This live cooking session explored the foundations of Japanese cuisine that have been passed down from the Edo period to present-day Tokyo.

From traditional preservation techniques developed before the advent of refrigeration, to methods of preparing seasonal ingredients, the chefs introduced the history of Tokyo’s food culture through both storytelling and cooking demonstrations.

Cooking and Ingredients that Emerged Alongside the Rise of Rice in Edo

Akihiko Murata

White rice, now the staple of the Japanese diet, became widespread during the Edo period. People reportedly consumed as much as five cups of rice a day, and it was during this time that the custom of eating rice together with various side dishes first began—a practice that continues in Japan today. As the rice culture spread, it brought with it new ingredients and cooking methods, helping to establish a nutritious and balanced culinary style that lives on in Japanese cuisine today.

Wisdom of Edo: Sustainable Food Culture Rooted in Tradition

Noriyuki Funyu

One such example was zuke-maguro—tuna marinated in soy sauce—a topping still commonly seen in Edomae sushi today. This method, which emerged during the Edo period, not only helped preserve the fish by leveraging soy sauce’s antibacterial properties but also deepened its flavor.

He also used aka-shari (red sushi rice), the traditional rice of Edomae sushi, made with vinegar fermented from rice malt. This vinegar had a reddish hue and was commonly used in preserved foods of the time.

Additionally, toro (fatty tuna), which was once considered too perishable and often discarded, was simmered with green onions as part of a hot pot dish—a clever way to make use of every part of the fish in an age without refrigeration.

In an age before refrigeration, these delicious dishes were created out of necessity and ingenuity—and even today, one can still savor them in modern Tokyo.

Celebrating Seasonal Colors and Aromas in Edo-Tokyo Cuisine

Kozo Nakayama

In Edo, the first produce of the season—hatsumono—was especially prized, and enjoying these early seasonal delights was considered iki (refined and stylish).

As a representative dish, he demonstrated sakura-dai kombujime with irizake. Kombujime is a traditional preservation method in which seasonal sea bream (sakura-dai) is gently pressed between sheets of kelp to prevent oxidation and enhance flavor.

Irizake, a tangy seasoning made by simmering sake with pickled plums and dried bonito, predates the widespread use of soy sauce in the Edo period. With lower salt content than soy sauce, it is now being rediscovered as a healthy and flavorful alternative.

He also prepared takenoko with kinome miso, a dish featuring bamboo shoots—a classic spring ingredient in Japanese cuisine.

Using a suribachi (Japanese mortar), he blended kinome (young sansho leaves), white miso, and spinach into a vibrant green paste. This technique, known as aoyose, adds color and aroma to the dish without overpowering the natural flavors of the ingredients.

We hope travelers visiting Tokyo will take the opportunity to enjoy the rich tastes of Japan’s seasonal ingredients at the city’s many restaurants that celebrate the beauty of the changing seasons.

Scene 02 The Modern Era

Harmony with overseas food culture Tokyo's unique

evolution and development

Since the Meiji era, a wide range of international ingredients and culinary styles have made their way into Japan.

Guided by a spirit of openness and adaptability, Japanese chefs embraced these foreign elements and harmonized them with traditional Japanese practices, leading to a uniquely evolved food culture in Tokyo.

This section features live demonstrations that exemplify the fusion of global and Japanese culinary traditions—an expression of the diverse and ever-evolving nature of Tokyo’s cuisine.

Italian Cuisine, Evolved in Tokyo

Yahei Suzuki

He began with a terrine made entirely from plant-based ingredients—a vegetable terrine with sun-dried tomato dashi—inspired by Shojin Ryori, Japan’s traditional Buddhist vegetarian cuisine. By using sun-dried tomatoes to create an umami-rich broth, the dish showcases a sophisticated fusion of Japanese dashi culture and Italian techniques.

Next, he prepared pesce crudo, a raw fish carpaccio that highlights cultural differences between Japan and Italy.

While traditional carpaccio in Italy is usually made with raw beef, in Japan—where fresh seafood is widely available and often consumed raw—the use of fish for carpaccio became a natural adaptation.

Finally, he presented a cold capellini dish that incorporated a Japanese twist: the use of crab meat—uncommon in traditional Italian cuisine—and a kelp dashi espuma (foam).

This creative interpretation reflects how Tokyo’s chefs, supported by high-quality ingredients and advanced supply systems, are able to craft unique dishes born from the harmony of global and local food cultures.

Innovative Gastronomy Where Japan Meets France

Yusuke Goto

One of the standout dishes was a savory crêpe inspired by the classic French galette, filled with wagyu beef and scrambled eggs. While the crêpe and eggs are rooted in French tradition, he added a distinctly Japanese element—shungiku (crown daisy), a signature ingredient in sukiyaki—by blending it into the crêpe batter. The result: a creative dish that evokes the flavor of sukiyaki while honoring both culinary traditions.

He also prepared Japanese hairy crab tartare with cauliflower crème and kelp jelly, combining seasonal ingredients from both Japan and France, as well as a monkfish meunière that highlighted the richness of Tokyo’s food scene, where top-quality ingredients from around the world are readily available.

Tokyo's Creative Culinary World: Where Techniques and Traditions Intertwine

Hideki Irie

Why is Japanese ramen so delicious and popular? The answer lies in Japan’s clean water and deep-rooted dashi (broth) culture. In Tokyo, many ramen shops place great emphasis on their broth, using techniques passed down since the Edo period.

During his demonstration, Mr. Irie guided the audience through a tasting experience of his signature dashi-based soup, adding one layer of flavor at a time: starting with a clear dashi broth, then adding shrimp soy sauce, followed by scallion oil, and finally green Sichuan pepper.

This step-by-step tasting illustrated the depth and complexity of dashi-driven flavor.

As a striking example of culinary innovation, he presented the Ramen Parfait with ikura and jellyfish—a layered dish that combined XO sauce-marinated jellyfish, whipped cream infused with aonori (green seaweed), crispy fried homemade noodles, and soy-marinated salmon roe.

This visually stunning dish reflects a fusion of culinary cultures from Hong Kong, France, and Japan, highlighting the creativity born in Tokyo’s kitchens.

Beyond ramen, Tokyo offers a wide variety of dishes where Japanese dashi culture and umami take center stage—demonstrating how deeply rooted traditions continue to inspire innovation in today’s diverse culinary landscape.

Scene 03 The Future

Sustainability and Diversity Learning from Japan's

ancient Shojin cuisine The future of Tokyo's food

Today, the world of food faces numerous challenges—ranging from environmental concerns to issues of race, religion, and food waste.

In this session, the discussion turned to how Shojin Ryori, Japan’s traditional Buddhist vegetarian cuisine, can offer insights and solutions for the future of food in Tokyo.

He shared the hope that Shojin Ryori, regarded as one of Japan’s oldest culinary traditions, could serve as a guiding light—not only in addressing environmental issues but also in offering inclusive solutions for a world with growing dietary needs due to increased inbound tourism.

At the same time, he emphasized a simple yet profound truth: “What matters most in food is that it’s delicious and brings joy.”

Tokyo is said to have around 100,000 restaurants—three times more than Paris. This abundance isn’t just about quantity; it reflects a thriving community of chefs constantly creating and evolving cuisine.

It is precisely this spirit of innovation that has shaped Tokyo’s richly diverse culinary landscape.

Hoba-yaki: mushrooms and vegetables wrapped in dried magnolia leaves and grilled, symbolizing the idea of reducing food waste by making use even of fallen leaves, while also reflecting diversity through the inclusion of international ingredients.

Hassun: a beautifully arranged seasonal platter that captures a moment in time—an experience unique to “here and now.”

Sankai-gohan: rice cooked with gifts from the mountains (mushrooms), the sea (kombu kelp), and the satoyama (countryside), expressing harmony with nature.

Shimizu-yose: a delicate, water-based dessert made of 95% pure water, celebrating Japan’s abundant and clean water as a unique national asset.

Each dish carried a message. They spoke not only to sustainability and seasonality, but to inclusion, creativity, and cultural identity.

“The future of food must be delicious and fair for everyone. True sustainability means satisfaction for farmers, chefs, and diners alike.”

With its clear water, fresh ingredients from across the country, and world-class chefs, Tokyo is uniquely positioned to lead the way toward a more sustainable and inclusive future of food.

We invite all visitors to experience Tokyo’s culinary heritage—one that has evolved from the Edo period, through modern times, and now continues to look ahead.